Mass media coverage of climate change – towards public engagement

by Karolina Martyniak

1. Introduction

Climate change is arguably one of the biggest challenges of the twenty-first century, which despite the heterogeneous nature of its impacts, will be felt across all locations and all sectors of society (Giddens, 2009). Addressing the problem effectively is of great significance, however, the lack of public engagement with the issue, that is currently observed, is considered as one of the main barriers in the transition to a low carbon economy (DTI, 2003). Indeed, lack of public acceptance and support has been shown to impede many renewable development projects in the past, such as wind power in the UK (Devine‐Wright, 2005). Moreover, the public contributes to carbon emissions, (Dietz et al., 2009; Gupta, 2011), whether it is directly (for example through domestic energy use), or indirectly (through the consumer choices they make), therefore, a sufficient level of public engagement with the issue is imperative in order to achieve meaningful emission reductions.

It has been frequently highlighted that the media exerts a significant influence on shaping public opinion (Carvalho & Burgess, 2005; Boykoff & Roberts, 2007), and this assertion forms the foundation of the premise of this article, that there is significant potential to revitalise and mobilise public concern and action with climate change through the mass media. Through a critical analysis of media conceptualisations of climate change, the article attempts to answer the following question: how could the media coverage be improved for a more effective communication and public engagement with climate change?

2. Mass media and climate change

The IPCC represents the mainstream scientific consensus on climate change (McCright & Dunlap, 2011). The panel’s information base is compiled through a careful examination of peer-reviewed scientific papers on the subject. However, the knowledge that is encapsulated in such literature is rarely ever directly available to, or absorbed by individuals. Moreover, it requires a ‘translation’ into simpler terms in order to be comprehensible for the lay public (Bell, 1994). It is thus mediated through a range of social and discursive practices (Doyle, 2011). In fact, despite the rapid development of climate change communication in the ‘new media’, the mainstream media still constitutes the single most significant source of information on issues like climate change for the general public (Anderson, 2011; Ryghaug et al., 2011). The media therefore has a significant effect on shaping public perception of the issue (Carvalho & Burgess, 2005). However, during the process of mediation the scientific consensus can become compromised due to common journalistic practices, with a knock on effect on perception. Therefore, an arrival at ways in which coverage can be improved for an effective engagement with climate change issues requires a careful analysis, which identifies influences that drive and shape media coverage.

3. Media coverage – the influences

‘The primary purpose of gathering and distributing news and opinion is to serve the general welfare by informing the people and enabling them to make judgments on the issues of the time’. – The American Society of Newspaper Editors (2013: 1)

This heuristic approach could actually prove problematic in safeguarding public engagement with climate change, and this section will provide some insights as to why that could be the case.

3.1 Journalistic norms

Many studies have reported that professional journalistic practices have a significant role in shaping media coverage in several ways. For example, Wilkins and Patterson (1990) demonstrate the importance of event-driven coverage. Boykoff and Boykoff (2004) on the other hand, highlight the distortion of scientific knowledge due to the journalistic norm of balanced reporting (see Fig. 1). Indeed, balanced accounts frequently figure in media coverage, because they allow journalists to ‘present the views of legitimate spokespersons of the conflicting sides in any significant dispute, and provide both sides with roughly equal attention’ (Entman, 1989: 30). This could be useful for journalists, because the majority do not have the necessary scientific background to interpret scientific data (Boykoff & Boykoff, 2007). However, conversely, this practice can be very damaging in terms of public engagement, because it produces an information bias. This occurs when the well-established, international discourse on climate change becomes distorted through an amplification of the sceptical discourse of global warming denial by the very practice of journalistic balance (Salazar, 2011). By giving a greater voice to the climate sceptics, the media legitimise their arguments creating an illusion of a scientific debate around the subject in the public eye (Reynolds et al., 2010). This confusion is further exacerbated by the language of probability and uncertainty that is often associated with scientific findings, whereby the general public mistakes the scientific uncertainty about precise climate impacts for scientists being unsure about climate change altogether. This is very problematic, because whenever the public senses a lack of scientific consensus around an issue, it is far less likely to support any actions targeted to address it (Lorenzoni et al., 2007).

Figure 1: Interacting Journalistic Norms (Source: Boykoff & Boykoff, 2007)

Note: This figure depicts the public arena of mass-media production, where journalistic norms interact. These complex and dynamic factors take place between and within (as well as feed back into) a larger context of political, social, cultural and economic norms and pressures (from Boykoff and Boykoff, 2007).

Another influential journalistic norm relates to novelty (see Fig.1). This holds that in order for coverage to be interesting, it must be new and exciting, because only in this way could it attract sufficient attention to the issue (Boykoff & Boykoff, 2007). This frequently results in a ‘repetition taboo’ (Gans 1979, 169), where stories that have already been published are rejected in favour of information that is fresh, original and current. This in turn leads to coverage that is highly sensationalised and full of catastrophic narratives invoked with fear and apocalyptic scenarios (Carvahlo & Burges, 2005). While it might capture the reader’s attention, fearful messages like these have been shown to have the opposite effect than anticipated when it comes to public engagement. Instead of evoking action, they make the reader feel hopeless and disengaged (Boykoff & Roberts, 2007). The study by Akerlof et al. (2010) found that people do not view themselves as vulnerable to the risks of climate change. Most people sampled think that climate change will harm plant and animal species (62%), future generations (61%) and people in developing countries (53%) a great deal or moderate amount (see Fig. 2); as opposed to themselves (32%) or their family (35%). This demonstrates that such journalistic practices lead to reduced risk perception, both in spatial as well as temporal terms (Whitmarsh et al., 2013). Indeed, scholars have frequently highlighted the central role of media in the social construction of risk (Pigeon et al., 2003; Mythen, 2004; Lorenzoni et al., 2005).The way in which they frame an issue could also contribute to this effect. It could be attributed to the environmental (discussed later on) or scientific framing. According to Nisbet and Mooney (2007)‘frames organise central ideas (…) they allow citizens to rapidly identify why an issue matters, who might be responsible and what should be done’ (p. 56).

Figure 2: Public perceptions of who will be the most harmed from global warming (Source: Akerlof et al., 2010)

The scientific framing for example, implies that solving climate change lies in the hands of the experts and policy makers. The responsibility is therefore effectively shifted from the hands of the general public. Moreover, the fearful narratives reinforce this further, making people feel hopeless and they start to exhibit fatalistic outlooks accompanied with the proverbial ‘drop in the ocean’ feeling. This refers to a conviction that one’s actions in relation to the rest of the world, will not yield any difference (Whitmarsh et al., 2013). However, this train of thought largely dismisses the power of individual actions which when combined, could account for a meaningful difference. This could lead to a significant proportion of the population disregarding the shear importance of the problem. Undeniably, research into public responses of scientific (and environmental) framing, suggests that such an approach to issue presentation does not promote the intended cognitive or behavioural outcomes, i.e. meaningful public engagement and collective action (Carvalho, 2005).

3.2 Visual imagery

Visual imagery is a powerful tool for media communication; the proverbial picture is worth a thousand words. Indeed, it could help convey meaning on issues that are difficult to visualise for the human mind, just like climate change. This refers to the Social Relations theory, of anchoring and objectification (Moscovici, 1984). Both of the themes are said to draw upon making something unknown, more comprehensible by bringing it into the sphere of something that is familiar, to aid comparison and enable interpretation (Höijer, 2010). However, many argue that the imagery that is often utilised for climate change could prove counterproductive (Moser & Dilling, 2004), and instead of promoting engagement, it could distance people from the issue.This is because climate change is often illustrated with pictures portraying nature, such as melting icebergs, or animals like polar bears, which fail to promote attachment with the issue due to being distinctly remote from people’s everyday lives (Doyle, 2011). This in turn, has a knock on effect on people’s risk perception, because the threat appears less imminent. Individuals therefore could start to exhibit an unrealistic sense of optimism in their ability to avoid risk (Weick, 1995),as illustrated by the discussion of Fig.2. This lack of personal sense of risk, in turn, could therefore help us to explain the lack of serious and sustained public engagement that we see with the environmental framing today (Cox, 2006).

3.3 Issue cycles & elite cues

When analysing media coverage on environmental issues, it is also useful to consider the theoretical framework of an ‘Issue-attention cycle’ proposed by Downs (1972). He postulates that public attention to issues like climate change, undergo five distinct phases, namely: (1) a pre-problem stage, (2) a period of alarmed discovery and euphoric enthusiasm to solve the problem rapidly, (3) the realisation of the costs associated with solving the problem, (4) a consequent, gradual decline in public interest, and (5) a post-problem phase, that is characterised by the settling of public attention and sometimes the sporadic return of interest (Downs, 1972). The premise of this framework underlines an assertion that the public finds environmental issues inherently unexciting, and therefore are unable to sustain prolonged levels of concern.

However, Brossard et al. (2004)on the other hand,argue that it is the journalistic norms practiced by reporters that influence the media coverage on climate change rather than the apparent public interest or otherwise, on the issue itself. They argue that ‘issues are not merely exciting (or unexciting) but are constructed as such’ (Brossard et al., 2004: 362). In fact, one of the main aims of the media is to narrate a story and to dramatize (Fischer-Lichte, 2001). This could be linked to the sensationalised coverage and the journalistic norm of novelty – the constant desire to shock and attract attention. Climate scepticism could actually prove quite useful to fulfil this need, because it often results in controversies associated with high issue salience (Entman, 1993). One of the most notable examples is ‘Climategate’, where the sceptics implied a manipulation of data after the hacked emails from Climatic Research Unit at UEA were leaked to the blogosphere (Bowe et al., 2012). It was an implicit allegation that questioned the legitimacy of climate scientists to tell the truth about global warming (Ladle et al., 2005). Some scholars have postulated that due to its careful timing (before international negotiations COP-15), this was an event of organised scepticism and a deliberate action to slow down the policy response due to the collision of scientific consensus with vested interests (Brulle et al., 2012; Hobson & Niemeyer, 2013). It later turned out that certain words were taken out of context; however the whole event received high media attention, which compromised people’s belief in climate change, adversely affecting engagement (Leiserowitz et al., 2013). For some, it resonated with core beliefs and values, which is closely related to the ‘Cultural Cognition’ theory (Douglas & Wildavsky 1982). In fact, it has been shown to have a strong influence on motivating individuals (Kahan et al., 2011). Indeed, Lorenzoni and colleagues (2007) assert that‘It is not enough for people to know about climate change in order to be engaged; they also need to care about it, be motivated and able to take action’ (p. 446).

4. Trends in coverage

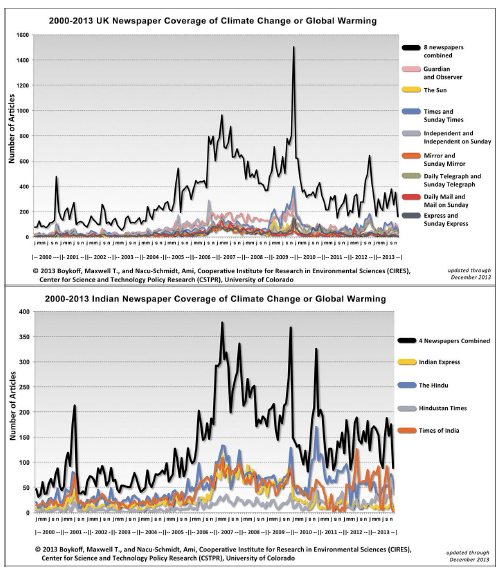

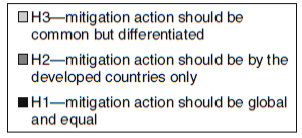

As we come to analyse the media coverage on climate change, we can see that a lot of the observed trends can be attributed to the media practices which modulate the news content. Current evidence points to a drop in coverage on climate change since 2009 (Boykoff & Mansfield, 2009; Scruggs & Benegal, 2012; see Fig.3).

Figure 3: The world newspaper coverage of climate change or global warming (Source: Boykoff & Nacu-Schmidt, 2013a)

This could perhaps be linked to the fact that climate change has been an issue since the mid-1980s (Moser, 2010), which goes against some of the journalistic practices (as discussed in section 3.1). It could also explain the rise in coverage during the big international events, such as the Conference of Parties in 2009. This is also when the controversy of Climategate occurred. Indeed, the coverage seems to follow elite cues, where issue-cycles can be observed. Moreover, public perception surveys reveal that public interest is also on decline; studies found that the percentage of people that believe climate change is real dropped significantly during that period (Prikken et al., 2011). Again, the way in which media reported the issue at the time had repercussions for public perception. Furthermore, all of this also coincided with a particularly harsh winter, which further exacerbated doubt in climate change due to its association with the term ‘global warming’ (Leiserowitz et al., 2010; Whitmarsh, 2011). Moreover, following from the Quantity of Coverage theory (Mazur, 1998 and 2009) the decline in media coverage on climate change communicates a message that the issue is no longer as important or relevant, which also leads to disengagement.

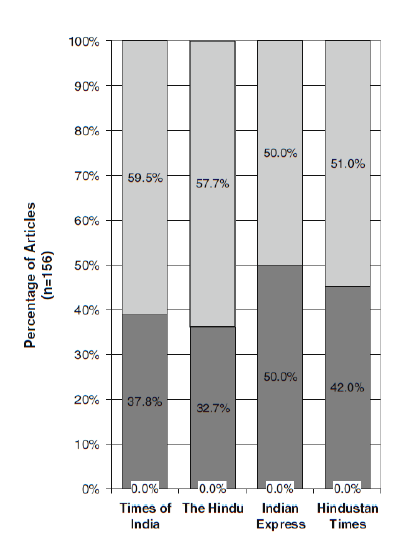

Similar trends in media coverage on climate change seem to be occurring in other countries, such as the UK and India, however India exhibits lower amount of coverage (see Appendix, Fig.4), because the issue is poorly covered by the local media (Kakonge, 2011).This could be becauseclimate change as a by-product of modernisation, poses a threat to India’s development. Indeed, when the issue is covered it is framed as a responsibility of ‘the North’ (Billett, 2009; see App., Fig. 5a-b). Interestingly, while there is a problem with climate scepticism in the UK, India’s coverage accurately reflects the scientific consensus on climate change (Billett, 2009).

While in the UK, the majority of the public is aware of climate change, this apprehension is not necessarily transformed into an accurate understanding of the problem or engagement with it (Lorenzoni et al., 2007; Scruggs, & Benegal, 2012). It is also important to note that if people have higher priorities, such as an economic recession, education, or the threat of terrorism, concern about climate change is likely to fall in their agendas (Poortinga & Pidgeon, 2003; Upham et al., 2009). Weber (2010) theorised that this is because people have a ‘finite pool of worry’ (p. 336). Moreover, going back to the third and fourth phase proposed by Downs (1972), people are not very willing to give up their carbon-intensive lifestyles, or take actions beyond recycling or domestic energy conservation (Whitmarsh et al., 2013). Indeed, Bolsen and Cook (2008) have empirically demonstrated that high energy prices associated with transition to a low carbon economy largely distance people from engaging with climate change.

5. Media coverage and public engagement

We have discussed what drives media coverage on climate change, and it became apparent that public perception and engagement with the issue closely follow the trends set out by the media. The media therefore holds the potential to revitalise and mobilise public concern and action with the issue.

In order to increase public engagement with the issue, and following the Quantity of Coverage Theory, the media should first and foremost increase the overall coverage on climate change. This will convey to the public that it is of high importance. Moreover, in countries like India, where the understanding of the issue is limited in some regions,more coverage would enable people to know how and why their environment is changing and they will then be able to demand action in their country (Slovic, 2000). On that note, it could also be useful to train journalists in the subject of climate change in order to improve the capacity of local journalists’ to cover the subject.

Reconsideration of fear appeals could also be useful, because they have been frequently shown to disengage. Nonetheless, they do have a role to play because they highlight the urgency of the issue; it is important to utilise them in a careful manner to avoid the potential disengaging effect.

Another important issue to take into account to improve engagement is personal relevance. Existing evidence suggests that in order to make the subject more meaningful and relevant, communication needs to take into account people’s worldviews and values. Utilising different frames of reference could be a solution here, because appealing to different sets of values has the potential to reach a wider audience.

An alternative approach could aim to appeal to common values, which could potentially be provided by framing climate change in terms of public health. Utilising such a novel frame makes sense, especially since climate change has been identified as the biggest health risk of the twenty-first century (Costello et al., 2009; WHO, 2012), with a potential to exacerbate existing health challenges (see Fig.6 for more details). Moreover, this could help to solve the problem of spatial and temporal remoteness between the abstract issue of climate change and people’s everyday lives. Indeed, some pioneering studies have found general receptiveness to issue reframing (Maibach et al., 2010). It therefore holds a high potential for effective communication of the climate change message and fostering enhanced public engagement with the issue. Moreover, this could provide the necessary stimulus to revitalise interest on climate change, as outlined by Downs (1972), (see section 3.3).

More coverage on mitigation and adaptation would also be beneficial. This is because focusing on solutions can empower people (Lorenzoni et al., 2007); and by providing them with ways in which they can address the problem, the media could reduce the problem of the ‘drop in the ocean’ feeling, and could thus help to facilitate public engagement with the issue.

Lastly, coverage should shift towards positive messages, which comes back to avoiding disaster narratives, and increasing opportunities or highlighting co-benefits of addressing climate change and making it more desirable for people to engage with (such as more jobs in the green economy as opposed to the low-carbon transition exerting a cost on the taxpayer). While this could be problematic due to the independent nature of the media, journalists should perhaps be encouraged to do this on the basis of fulfilling the media’s purpose of acting in the public interest. Since climate change will affect all sectors of society, it is imperative to make it our common goal, and the media has a strategic role of servings as a platform of opportunity when it comes to enhancing public engagement with the issue.

Appendix

Figure 4: Newspaper coverage of climate change or global warming: comparison of UK and India (Source: Boykoff & Nacu-Schmidt, 2013b, 2013c)

Figure 5a: Framing responsibility for climate change in the Indian media (Source: Billett, 2009)

Figure 5b: Framing responsibility for climate change mitigation in the Indian media (Source: Billett, 2009)

Figure 6: Pathways by which climate change affects human health (Source: Haines et al., 2006)

Pingback: Climate change: “She’ll be right” in the sunburnt country | Giverny Witheridge